Date Posted:

Wednesday, November 24, 2021

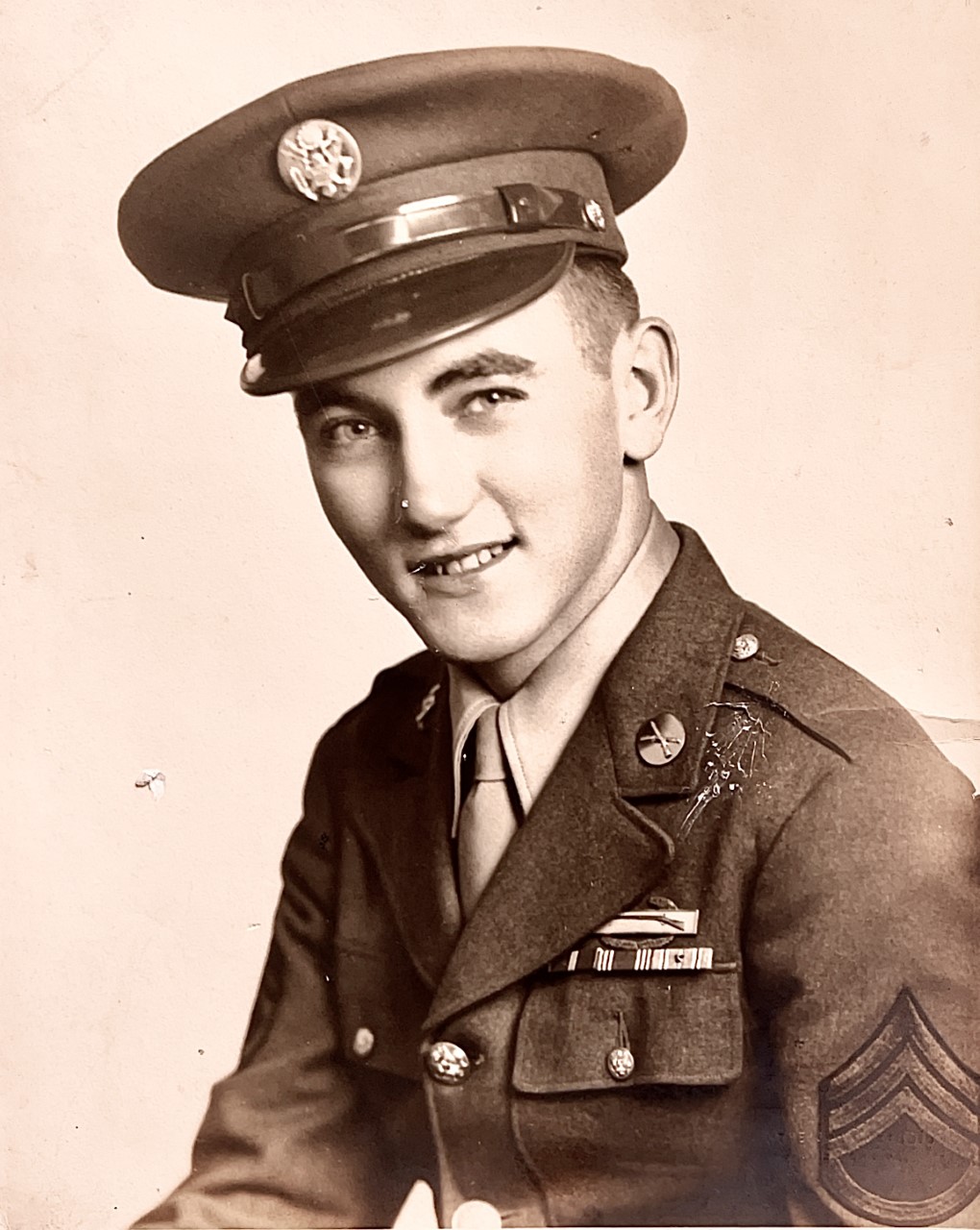

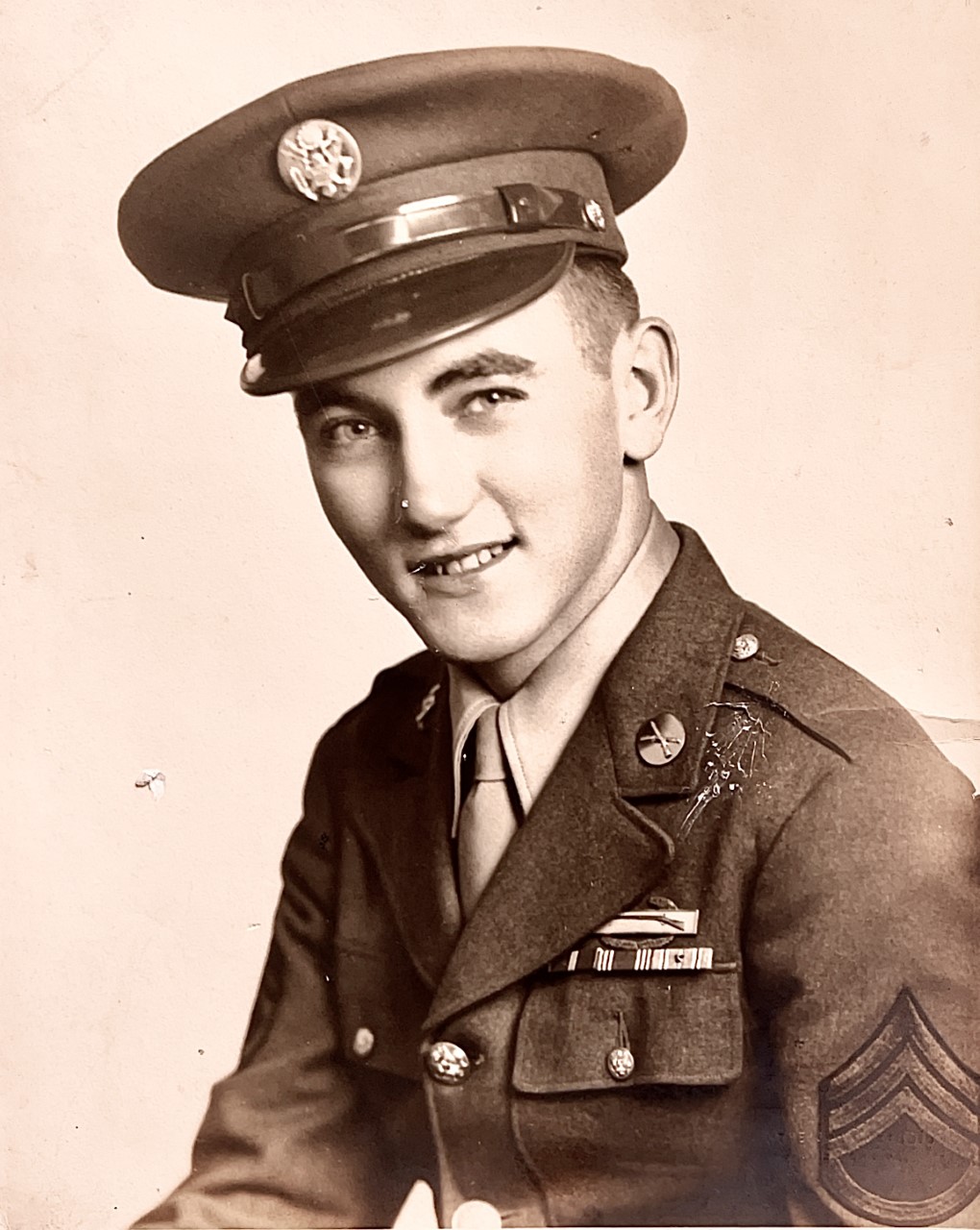

Harry Isabel '43

December 2021

By Harry Isabel '43

It was 1943 when I graduated high school from Fork Union Military Academy and immediately enlisted in the army. I entered active duty on August 18,1943. My basic training was at Camp Roberts, California and I was informed I would enter ASTP (Army Specialized Training Program) following basic. I suppose they needed me more as a combat soldier, because my next post was a short stint at Fort Ord, then to Schofield Barracks. I was assigned to Company B of the 165th infantry (“fighting 69th”) of the 27th division. The 165th guys were tough dudes of the New York National Guard and had vocabulary unknown to this small-town Uniontown, PA kid, one of the youngest in the company, to be known as Junior.

We watched as we bombarded Saipan, day and night, for probably 3 days from ship and air, and in the middle of one night we were ordered to assemble on deck with full gear and line up to begin the descent into the awaiting LCVP’s (landing craft, vehicle, personnel or Higgins boat). As we neared shore we just stopped and were told to climb over because the coral reefs prevented a beach landing. Over we went. Fortunately, my feet hit something solid and my head was above water. I threw most everything away, keeping water, ammo, helmet, etc., and held the rifle above my head. (The M1-The rifle that won the war). Many crafts were forced to abort a landing. However, there was not as much confusion as you might expect, and we reached the beach. As I recall there were sporadic mortar/artillery drops but no small arms concern since the Marines had claimed the beach the previous day. However, the sight of dead enemy soldiers, both bobbing in the water and beginning decay on the beach, was unpleasant.

The logistics of the whole operation (and the war effort at large) was unbelievable. The timely delivery of all necessities was outstanding, including water, ammo, food rations (C, D, and K). Our movements were cautious and challenging due to undergrowth, excellent positioning of plantings, years of pillbox placements, great sniper positions, use of caves, and well-planned entry and exit (of the enemy troops) of same. The Japanese had a network of caves all over the island...

On June 24th, on an advancement, I was awaiting a forward move when I heard a volley of Japanese machine gun along with considerable mortar fire. The machine gun had an eerie, pop pop pop sound to me, possibly of a lesser caliber than ours. However, then came human screams the like of which you have never heard. Some of our guys had been hit. I was behind a pile of rocks and all of a sudden a voice said “Is that you Isabel?” I knew the voice, as it was our Company Commander, Captain Gil. I was shocked as I didn’t even realize he knew me. I said, “Yes Sir”, and he said, “How old are you Isabel?” I said “eighteen Sir but I’ll be nineteen in a few days”. He said “I hope you make it because those screams are coming from (and he named the injured fellow soldiers, one being a Lieutenant) and if you are with me, we are going up there and get them medical help”. I said “Let’s go”, and we did. We took off and reached our critically wounded amid some crossfire. I won’t discuss the condition of the guys but we were able to get aid and help for those who survived that incident.

A few months later, after the battle, we went to Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides islands (now Vanuatu) and I was called to the Captain's quarters. Captain Gil informed me that there would be an awards ceremony parade and I would be the recipient of the Bronze Star. He was quite perturbed when I asked: “What for?”. After a slight chewing out, he told me that he had recommended the Silver Star but the review board reduced it to Bronze. I would guess Captain Gil to have been in his 30’s, a New York guy, solid, knowledgeable, compassionate, and with humility as well as being an excellent leader.

“What the hell! It looks like you took a hit”. I said, “I didn’t take a hit” and “Is it bad?” He said, “Not too bad”. I told him to patch it and send me on my way. He told me he would write me up for the Purple Heart, I said, “No way”. My reasoning was I had seen many who deserved the Purple Heart for serious wounds. Also, I didn’t want my parents to be informed that I was wounded causing them to worry about me.

Anyone who has served in the military know that nothing is routine in combat, so we continued our slow but sure movements forward. I kept looking at Mount Tapochau, the highest point on the island, and with youthful exuberance decided (dreaming) once we were over that hill all would be easier. The nights were long and wet and the days were long and hot. During the nights we took turns on guard. and fortunately, we did not suffer the Banzai charges, as did the 105th infantry. The “edge” was constant, during nightly duty, because many guys “saw something” and either fired in that direction or lobbed a few grenades. There was never quiet time.

Their (Japanese) years of buildup, in anticipation of this very battle, added some difficulty to finishing off a group who had to know they were facing defeat. We continued our movements north, cautiously, with the expected dealings of the enemy snipers, machine guns (out of their well-positioned locations) and continued mortar fire. There were never attempts at surrender. By the time we reached the northern tip of the island many civilians and Japanese soldiers had jumped to their deaths from the cliffs. Their bodies were evident in the sea and rocks below. Although the battle officially ended on July 9, some Japanese resistance persisted and many sought escape throughout the island.